Development of BART Demanded Decades

Development of BART Demanded Decades

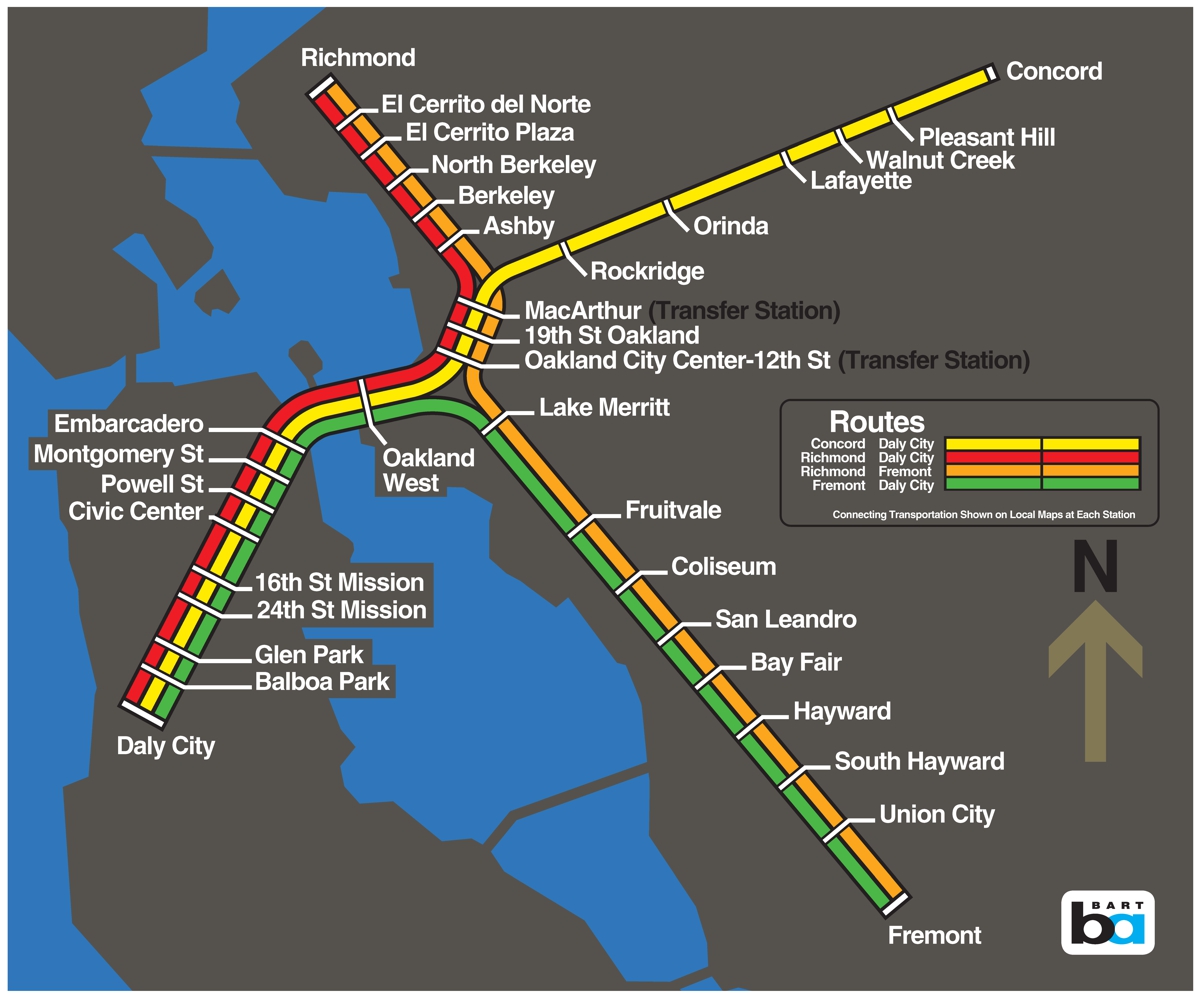

Bay Area Rapid Transit, most commonly known as BART, celebrates its 50th anniversary in September. Hacienda business tenants and residents already know the value of having a BART station nearby. With frequent trains serving the Hacienda BART station, employers at Hacienda have access to labor pools far beyond the traditional car commute. College students and shoppers also have easy access to institutions and shopping districts across BART's five lines, which serve portions of Contra Costa, Alameda, San Francisco, Santa Clara, and San Mateo counties.

Note to our Readers: BART's fifty year history has much to relate. We will be covering this important milestone in two stories. Please enjoy this first installment which will relate BART's formation and early days. Next month's story will cover more recent events including the opening of the BART station in Hacienda and what BART has meant to the Tri-Valley.

BART opened to revenue passenger service on September 11, 1972 with Fremont to Oakland service that included 28 miles of tracks and 12 stations, according to BART officials. During its first week of service, 100,000 riders took BART, which then used two-and three-car trains. Toward the end of that month, President Nixon himself took a ride on BART. Fifty years later, the value of BART may seem obvious to current riders but the development of this modern transit system and its eventual structure were decades in the making.

How it Began

The agency's official Historical Timeline traces the beginning of BART's existence to a January 1947 joint Army-Navy report that "recommends action for underwater transit tube beneath San Francisco Bay to help address growing bridge and freeway congestion." The interest in a new transit system found favor in several quarters. The Law and Legislative Committee of Electrical Workers Local 6, for example, wrote a multi-part analysis of the proposal for a Bay Area rapid transit system.

"New industries coming to the Bay Area are, for the most part, setting up outside of the City of San Francisco," noted the committee in Part 2 of its analysis, which appeared in the July 10, 1948 Organized Labor newspaper. "The fact that our transportation within San Francisco is not yet satisfactory, is only one of the reasons that industrial plants are going elsewhere within the Bay Area. It appears the main reason industrial plants are going to spots outside of San Francisco is that our city is too congested. The industries want space. They want locations where trucks carrying materials to and from the plant can get in and out quickly, make deliveries quickly."

"... transit facilities between the East Bay and San Francisco are too slow," argued Part 4 of the analysis, in the July 24, 1948 issue of Organized Labor. "The Bay Bridge has almost reached its capacity to accommodate private automobiles, which if they do get here have to fight traffic, and motorists can't find a place to park. Thus San Francisco stands to lose materially because of Bay Area traffic congestion and lack of adequate transit facilities. The remedy is BAY AREA INTER-CITY RAPID TRANSIT. To bring this ‘dream' into being will be a tremendous undertaking, but it MUST BE DONE."

The Electrical Workers Local 6 was not alone in supporting a new rapid transit system. "In the late 1940s and early 1950s, small groups of interested citizens, principally representatives of commercial enterprises led by executives of major San Francisco corporations, sowed the political seeds that eventually grew into a $1.6 billion mass transit system," according to the authors of A History of the Key Decisions in the Development of Bay Area Rapid Transit, which was created for the US Department of Transportation and the US Department of Housing and Urban Development in September 1975.

The rapid post-war growth in California and the Bay Area made transit an ongoing issue. In a 1956 report called Regional Rapid Transit, an engineering firm working for the San Francisco Bay Area Rapid Transit Commission echoed the concerns heard in the 1940s. "Today's age of automobiles has brought with its miracles a level of travel discomfort, cost, and hazard that is critical," the report noted. "In the Bay Area, home now for some three million people, traffic problems are aggravating. With the population forecasted to increase by more than fifty percent in the next fifteen years, they loom as staggering… We are convinced that the easy exchange of people and goods from one part of a metropolitan area to another is vital to its economic, social, and cultural welfare."

Early Milestones

Despite the enormous scope of the project, the dream of BART was accomplished–but not without some changes along the way. In the late 1940s, early BART proponents encouraged a nine-county system; in 1957, the California Legislature approved the creation of a Bay Area Transit District with five counties only. According to BART officials, initial funding for the project was not raised until November 1962, when District voters approved $792 million in General Obligation Bonds for construction of a 75-mile system. With that funding in hand, progress began on the system we know today, and in June 1964, President Lyndon B. Johnson presided over the official start of construction at the site of the future Concord station.

The Transbay Tube structure was completed in August 1969. Four years later, in August 1973, the first test train traveled through the Transbay Tube from the East Bay to Montgomery Station in San Francisco. In September 1974, Transbay service began for paying customers. Throughout its early years, BART accomplished a number of milestones. In July 1975, the agency adopted a 75% fare discount for people with disabilities, which was an industry first, according to officials.

Other milestones included extended hours of operation, from 6 am to midnight, in January 1976.

That same year BART also "increased commute train lengths on all lines with ten-car trains, seating 720 passengers," officials say. Another noteworthy development occurred in July 1986, when BART completed a fire-hardening program on all transit vehicles, which made "BART cars the most fire-safe transit vehicles in the country."

A few years later, BART played a pivotal role in the Bay Area after a 7.1 earthquake in October 1989 devastated parts of the Bay Area. Because the Bay Bridge was forced to close, thousands of commuters began using BART for the first time. An uncounted number continued using the system even after the Bay Bridge reopened in November 1989.

In September, BART plans a day-long community celebration for its 50th birthday to be held at its Lake Merritt station in Oakland. Regular riders know there are many reasons to celebrate. They include easy access to Bay Area cities and a convenient commute system for people at Hacienda.

For more information about the history of BART and the upcoming celebration, please visit www.bart.gov.